Busing, Segregation, and Education Reform in Boston

This year, the Catholic Campaign for Human Development is celebrating 50 years of hard work that addresses the root causes of poverty in the United States. Throughout the year, we've been highlighting several initiatives and organizations that facilitate this mission in cities around the country. We recently showcased organizations fighting homelessness in LA, advocating environmental justice in Portland, and more.

Now we head to the east coast -- Boston, to be exact -- to highlight the on-the-ground work some of our community organizations have been doing in order to create accessible, quality public education. But in order to understand why their work is so essential, it's important to understand some of the history and racial/economic divisions that afflicted the city, the effects of which are still observed today.

The Boston Education System: Segregation and Economic Turmoil

Boston and the neighboring city of Cambridge have been heralded as bastions of world-class education for ages. Prestigious schools can be found throughout the region -- and include 54 colleges such as Harvard, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Tufts University, and countless private schools, housing around 250,000 students at any given time and making it one of the great education capitals of the world. But despite these highly sought-after, elite institutions, there are two sides to every coin; and there is a darker story to be told about Boston's public school system. It is one of complex legislation as well as racial and economic inequality.

It’s important to remember that the process of school desegregation began just 60 years ago, and is only one step toward breaking down centuries of racial inequality. It is crucial to understand the effects of these constructs, how they manifested, how they were dealt with, and how we currently deal with them, in order to understand why we are where we are today.

Segregation and Controversial Solutions: Busing in the 1970s

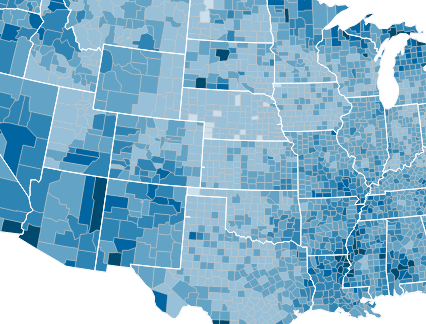

Like most of the country in the early 19th century, Boston practiced segregation through legislation such as redlining, a series of housing policies that deliberately prevented communities of color from owning property in white neighborhoods. In this way, those in favor of segregation were more easily able to deprive communities they deemed "lesser" of quality public services such as education.

Eventually, thanks to the tireless efforts of civil rights activists, courts mandated the desegregation of Massachusetts schools through the Racial Imbalance Act of 1965, which stated, "racial imbalance shall be deemed to exist when the percent of nonwhite students in any public school is in excess of fifty percent of the total number of students in such school." State officials decided to facilitate school desegregation through 'busing' -- the practice of shuttling students to schools outside of their home school district. In essence, some suburban, often white children would begin attending urban schools, which were often predominantly students of color, while Black children were bused to the suburban, majority-white schools. The theory behind this practice was that transporting students to outside districts would diversify schools and encourage equality in education.

However, Boston's busing policy would not go uncontested. Outrage throughout working-class white communities was loud and some local government and community officials made their careers based on their resistance to the busing system. Eventually, once busing first began in 1974, tensions boiled over in the mostly-white, working-class neighborhoods.

South Boston High School even drew national attention due to outspoken community leaders. They staged protests, riled up parents, and resisted the new diversity-driven policy in vain. The school became a racial battleground. On the first day of busing implementation, only 100 of 1,300 students came to school at South Boston (while only 13 of the 550 former South Boston students ordered to attend Roxbury High School -- a majority black student school -- reported for class). Parents and students alike took to the streets in protest as the very first bus arrived alongside a police escort. White students threw rocks and chanted racial slurs and disparaging comments such as, "go home, we don't want you here" at their new, Black peers. This continued every day, resulting in race riots and, eventually, racially motivated violence.

The Soiling of Old Glory, a Pulitzer prize-winning photograph taken by Stanley Forman during a Boston busing riot in 1976, in which white student Joseph Rakes assaults lawyer and civil rights activist Ted Landsmark with the American flag.

A few lives were tragically lost during the brief outbreaks of violence. Regardless, the practice of busing continued until 1988, when a federal appeals court ruled that Boston had successfully implemented the desegregation plan and was fully compliant with civil rights laws.

The history leading up to the formation of busing policy in Boston is long, complex, and most of all an insight into the attitudes that perpetuate systems of injustice. The Atlantic's The Lasting Legacy of the Busing Crisis does a great job of contextualizing the period within a larger civil rights movement picture:

"School desegregation was about the constitutional rights of black students, but in Boston and other Northern cities, the story has been told and retold as a story about the feelings and opinions of white people. The mass protests and violent resistance that greeted school desegregation. . .engraved that city’s 'busing crisis' into school textbooks and cemented the failure of busing and school desegregation in the popular imagination. Contemporary news coverage and historical accounts of Boston’s school desegregation have emphasized the anger that white people in South Boston felt and have rendered Batson and other black Bostonians as bit players in their own civil-rights struggle."

The Lasting Effects of Busing: Bad and Good

The Boston busing riots had profound effects on the city's demographics, institutions, and attitudes:

- Boston public school attendance dropped by ~25% because white parents did not want to send their kids to school with Black children.

- Urban whites fled to suburbs where busing was less fervently enforced.

- South Boston High School became one of the first schools in the country to implement metal detectors after a near-fatal stabbing during the protests.

- More than 500 police officers guarded South Boston High School every single day.

- 78 schools across the city closed their doors for good.

- Boston's busing system ended in 1988. By that time, the Boston public school district had shrunk from 100,000 students to 57,000.

- Today, half of Boston's population is white, but only 14% of public school students are white.*

*Some point out that even before busing policy began, the city's demographics were heavily shifting. It is hard to exactly quantify the role busing played in these shifts, but it certainly was a contributing factor.

In the end, busing did not achieve the racial harmony and equality it strove for, due in no small part to white families fleeing the city. Regardless of some of these negative effects, some good did come from busing. For one, it validated the claims that civil rights leaders were espousing -- that the Boston education system favored one race over the other.

" 'When we would go to white schools, we'd see these lovely classrooms, with a small number of children in each class,' Ruth Batson [local civil rights leader and parent of 3] recalled. . . 'The teachers were permanent. We'd see wonderful materials. When we'd go to our schools, we would see overcrowded classrooms, children sitting out in the corridors, and so forth. And so, then we decided that where there were a large number of white students, that's where the care went. That's where the books went. That's where the money went.' " (source)

Once white students started attending predominantly black schools, those schools actually started to see some increases in funding.

There is no doubt that busing was and still is a controversial issue, but the fact remains: progress is often met with resistance. Something had to give in order for communities of color to provide a brighter future for their children, and at the time, this was a step toward those goals.

Many point to the Boston busing riots as an example of failed desegregation, despite the fact that other parts of the country saw immense success through similar programs that got little to no media attention. Additionally, busing had immense support in multicultural communities across the country. While a few thousand here and there would march against busing, one rally in 1975 saw more than 40,000 people come out to defend the new busing policies:

"'We wanted to show Boston that there are a number of people who have fought for busing, some for over 20 years,' explained Ellen Jackson, one of the rally's organizers. 'We hoped to express the concerns of many people who have not seen themselves, only seeing the anti-busing demonstrations in the media.' Despite the media's focus on the anti-busing movement, civil rights activists would continue to fight to keep racial justice in the public conversation." (source)

We must not forget that busing in Boston was the culmination of a decades-long civil rights struggle led by communities of color and activists striving for a better future for their children. Violence and strife get the limelight while restrictive government policies that kept communities in overcrowded, underfunded schools get no attention. Policies that denied a political voice to working-class and disenfranchised communities went ignored up until that point. Busing policy was an effort to break that cycle of poverty and, despite some of its notable failures in Boston, was a step in the right direction for racial and economic equality.

The Boston Education System: Where it is Today

Today, Boston's total population is only 13% below the city’s 1950 high level, but the school-aged population is barely half what it was in 1950. There are many reasons why this is the case, including the fact that the city currently mainly attracts higher-income, childless young professionals, probably due to the city's ~250,000 college students at any given time. Thanks to immigration, high-paying jobs, and academia, the city's population has largely rebounded since the white flight that came with busing, though fewer and fewer young families are choosing to reside within the city due to rising property values. According to a recent study of Boston urban and suburban school demographics:

- Almost 8 in 10 students remaining in Boston’s public schools are low income (77 percent as of 2014).

- Almost 9 in 10 are students of color (87 percent as of 2019, almost half of whom are Latino). This has created a growing mismatch between the demographics of children who attend Boston’s K-12 public schools and the city overall.

- The city’s overall population is “more than three times as white as Boston’s public school population,” the researchers found. And while the city itself may be “far more diverse” than it was decades ago, its schools have become “far less integrated.”

- Researchers found that more than half of the city’s public schools are now “intensely segregated.”

White flight to the suburbs during and post-busing played no small part in shifting urban school demographics. Today, inner city public schools are mainly utilized by lower-income families and communities of color. All of these statistics and historical context are crucial in understanding why it's so important for great community organizations to provide quality education and lend equal opportunities to children of all backgrounds, regardless of race.

CCHD-Supported Organizations That Improve the Boston Education System

- GBIO (Greater Boston Interfaith Organization): GBIO is a member institution dedicated to making Greater Boston a better place to live, work, and raise a family. For over 20 years, they've helped improve housing, healthcare, criminal justice, and education through addressing racial disparities between communities. For instance, in 2014, they completed a project that, "fought and won a battle to replace the deteriorating Dearborn Middle School with a $73 million, state-of-the-art grade 6-12 STEAM academy for students in its under-served Roxbury neighborhood."

- MCAN (Massachusetts Communities Action Network): For over 30 years, MCAN has striven to create better Boston communities through community organizing and empowerment. They believe that instilling a deep loving commitment to each other will make us realize that people are more important than the structures of our economy. Recently, they celebrated a massive victory for the passage of the Student Opportunity Act, which allocated $1.5 billion into school districts. "Currently, there are many struggles for students with remote learning. Some students cannot get computer or internet access, some students and their families have not connected with the schools at all in this period, and some students only participate sometimes. There is a huge challenge for households with adults working outside the home to give support to their children during the day while remote learning is supposed to happen. This disproportionately impacts people of color, low income, English language learners, and students with special needs."

Take Action in Your Community

Help us amplify the work of these CCHD-supported groups working to bring access to quality education to every child in Boston by sharing this article on social media, donating, or volunteering. Be sure to follow us on Twitter and Facebook for more information about how you can join the work to break the cycle of poverty in your city.

Are you looking for additional ways to take action in your community? Visit our Take Action or our Support webpage.

About Poverty USA

Poverty USA is an initiative of the Catholic Campaign for Human Development (CCHD) and was created as an educational resource to help individuals and communities to address poverty in America by confronting the root causes of economic injustice—and promoting policies that help to break the cycle of poverty.

The domestic anti-poverty program of the U.S. Catholic bishops, CCHD helps low-income people participate in decisions that affect their lives, families, and communities—and nurtures solidarity between people living in poverty and their neighbors.